It’s only too common that organizations and governments bring funds and programs to communities that have been marginalized, only to end up finding that what they create is not even used by the people its designed for. The concept of co-design strives to change this pattern, opening new and more socially just ways of interacting with each other and sharing power. In this episode we talk with conservation psychology expert Kayla Cranston around the question: can working together can make us both more effective and also make our actions more just and inclusive?

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google | Simplecast

Episode Notes

Visit Antioch’s website to learn more about the School of Environmental Studies and Sustainability that Kayla is faculty in. It offers a study of conservation psychology at the certificate, bachelor’s, Master of Science, and PhD levels. We encourage you also to read Kayla’s paper in Zoo Biology and our Common Thread article looking back at the Co-Design project after its first year. Kayla teaches an open-enrollment course through the UC San Diego extension called “Co-Designing Conservation.”

This episode was recorded December 21, 2022, via Riverside.fm and released February 8, 2023.

The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch University

Host: Jasper Nighthawk

Editor: Johanna Case

Digital Design: Mira Mead

Web Content Coordination: Jen Mont

Work-Study Intern: Sierra-Nicole E. DeBinion

A special thanks to Karen Hamilton, Amelia Bryan, and Melinda Garland

To access a full transcript and more information about this and other episodes, visit theseedfield.org. To get updates and be notified about future episodes, follow Antioch University on Facebook.

Guest

Kayla Cranston, PhD is the Director of Co-Design Science & Innovation at Antioch University’s New England campus. In this position, Kayla leads the design and administration of a suite of professional development services to strengthen the capacity of conservation professionals to integrate Conservation Psychology into their daily work effectively. Previous to this post, Kayla worked at Saint Louis Zoo as a Conservation Education Researcher, where she led the evaluation of K-12 environmental education programs and designed and managed a co-design project that strengthened the capacity of the zoo to co-develop zoo programming with (not for) the community of North St. Louis County.

S5 Episode 2 Transcript

S5E02: Kayla Cranston

Jasper Nighthawk: [00:00:00] This is the Seed Field Podcast, the show where Antiochian share their knowledge, tell their stories, and come together to win victories for humanity. I’m your host, Jasper Nighthawk, and today we’re joined by Kayla Cranston for a conversation about an approach to environmental conservation projects that Kayla calls Co-Designing Conservation With, Not For, Communities.

Let me give a brief introduction for why this is such an important subject today and why I’m really excited to have a chance to talk with Kayla about it. We’re recording this, it’s the early 2020s, and I think we’re at a moment where it feels like a critical mass of people are ready to address climate change and the environmental disasters that are occurring, in every part of our world.

It’s terrible that our planet is in so much distress, but thank goodness we’re finally seeing some action at governmental levels and certainly at the levels of mass movements and also at [00:01:00] the levels of specific organizations. At the same time as governments spend more money and organizations around the country and world focus their efforts on these questions, there’s I think a real question of whether the patterns that got us to this place will continue.

And here I’m thinking specifically about patterns where power is wielded by a few people. A few people are empowered to make these big decisions and they dictate how things are gonna be for the many. And I think that we’re at this turning point where there’s an opening for a new and more socially just way of interacting with each other and really sharing power.

is it possible that working together can make us both more effective and also make our actions more just and inclusive? I suspect I know what Kayla’s answer is, but we’re also gonna talk about how specifically we might go about doing that.

Kayla Cranston, our guest today has been asking this question for a long time now. She is faculty in Antioch’s School of Environmental Studies [00:02:00] where she in fact, got her own PhD. She is also our Director of Conservation Psychology Strategy and integration. Her work in her career has taken her to many different countries around the world, and she’s worked with many prominent organizations, including the American Museum of Natural History.

And what we’re gonna be talking about today is her recent paper, which she wrote with some co-authors, that was published in Zoo Biology, and it’s titled Five Psychological Principles of Co-Designing Conservation With, Not For, Communities. We’re gonna link to that paper in our show notes. I recommend people go read it, it’s not that long. It’s very interesting. And we’re also gonna talk about a big co-designing project that she’s leading here at Antioch. This collaboration has Kayla and her team applying these principles with zoos and aquariums across the country. Currently, they’re working with Franklin Park Zoo in Boston, Cleveland Metro Park Zoo, the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, and the Detroit Zoo.

So with all of [00:03:00] that, welcome to the podcast, Kayla.

Kayla Cranston: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me.

Jasper Nighthawk: I’m so excited to get into these questions, but something that we like to do when we start our interviews is take a minute disclose our positionality so that our listeners have some context for where we’re coming to this conversation from. I’ll go first. I’m white. I’m a cisgendered man. I’m not straight, but as a man, married to a woman, I move through the world with a lot of straight privilege.

I’m not currently living with a physical disability, though I do experience anxiety and depression and have been treated for them on and off for years. I have stable housing and I have full-time work, which don’t take either of those for granted either. Kayla, as much as you’re comfortable, can you tell our listeners where you’re coming to this conversation from?

Kayla Cranston: Yeah, and Jasper, thanks for asking. That’s definitely one of the first times I’ve had an interview start like that, so I think it’s really important. I am a cisgendered a woman, and I am straight [00:04:00] and I like you, I’m not living with a, a physical disability. However, I have, over the majority of my life, struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder from some very early abuse that was in my family and has actually kind of led me to this work empowerment.

Kayla Cranston: Um, I currently have stable housing and I also have full-time work. let’s say a little more than full-time work, right now, which is why, you know, building capacity for this kind of thing outside of Antioch is, also really important.

Jasper Nighthawk: Thank you so much for sharing that, Kayla, and I want to get into what brought you to this work, but I think it’s generous of you to kind of share these personal things. You know, I think the personal is always connected to the professional and to everything else. S So let’s get into it. I want to talk about this concept of Co-Designing With, Not For, Communities, which I’m gonna say a bunch here, and hopefully [00:05:00] it’ll kind of make sense to listeners.

Like that the, “not for” is in parentheses. Co-Designing With, Not For, Communities. So maybe a good place to start is to actually ask you how did you come to learn about this concept and what drew you to it and caused like, put your own spin on it and kind of make your career around it.

Kayla Cranston: That’s a really good question. My academic training is in psychology, social and behavioral psychology specifically. It’s what I’m good at, right? It’s what I was kind of groomed to be good at, in a chaotic living situation growing up. And even though my heart has always been in conservation, you know, my skillset is in reading people and working with people, in essence, attempting to help others create structures that will allow their power to be seen and to be heard. And so that’s kind of like the passion piece, I suppose.

However, when we’re talking just about co-design and this model, that came [00:06:00] much later in my schooling. So I went and the undergrad in psychology and the master’s degree in sustainable community development. really my doctorate was focused on how can psychology help conservation move forward. that’s what I’ve always wanted to do. It’s what I’ve been doing for quite a while, and the co-design piece came as an answer to that. So I was taking a sustainable community development course by Dr. Tanya Schussler. I did receive my doctorate here at Antioch in the same department, that I’m working now And when I was here doing my doctorate, I took this course by Dr. Schussler and there were many different models of community engagement that were being put forth as potentials.

Right? And they were on this spectrum that they called the Pretty spectrum. And it’s called the Pretty Spectrum because it was made by this guy named Jules Pretty, and essentially on one [00:07:00] side of it was let’s engage the community in conservation, so far that we’re educating them, right? We’re letting them in on, on a decision we’ve already made. And so that can look anything like a workshop or training or a pamphlet, things like that. And the other end of the spectrum of community engagement looks more like handing over the reins, just to the community and allowing them to go for it. Right.

Jasper Nighthawk: It’s almost like a block grant. Like here’s some money, we’ll check

Kayla Cranston: Exactly like, we’ll we’ll see. Yeah. It doesn’t even matter what you do with it, see you later. So, we introduced to the spectrum of different community engagement processes and then the class ended. And no guidance given as to which one might be best, how do you know which one you should be choosing. And I as a psychologist, uh, Scientist who’s doing quantitative psychology. I wanna know hard answers. I need to know like which of these approaches is [00:08:00] the best? And how do you know and how can you go and therefore test for it. the reality was that at the time there wasn’t a tool to really choose between these, models .

So, yeah, exactly. And so for one of my final projects for that class, I ended up just combining a whole bunch of them and saying, if you can, put these together in a way and find a metric that will help you determine what is working best for the specific context that, that itself will be how you can tell which is best. Right? And so the, the models that I combined. it was, everything from Pretty himself, to Driscoll, and Louise Chala, and participatory asset mapping. Put ’em all together, and, added a few extra pieces myself, that when I created the tool that would help us determine which version of it would work for which context, I found to work the [00:09:00] best. And so that’s how I came about it.

Jasper Nighthawk: That’s pretty much what, what led you to this? Well, now might be a great time to kind of give your elevator pitch description of what Co-Designing With, Not For, Communities, is.

Kayla Cranston: Sure, so Co-Designing With, and Not For, Communities, is a community engagement technique. It’s a method. It’s a, it’s a process more than anything. And it is one that is specifically aimed at bringing the voices that have historically been excluded from conservation conversations, and quite honestly, many community cons, conversations that are had by conservationists, without knowing that those decisions made will impact the community. So it’s about including those individuals who have been historically excluded from those conversations and doing [00:10:00] it in a way that is really holding up what we’re doing to the standard that is set by the community.

And the whole theme of Co-Designing Conservation With, and Not For, Communities, is that it isn’t for communities. We aren’t doing this, for them. We’re doing this with them. And so the difference between those two things is the difference between saying, you know, “if you build it they will come,” and the the difference between that and saying something along the lines of, ” if you build it with them, they’re already gonna be there and they will have ownership over it and therefore they will be able to work with you to continue its success over time.”

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah, I was thinking about that. “If you build it, they will come.” And I was thinking about how many projects I have seen out in the world where things are built and the people never really come, know, a community. Yeah, like a community park or something. And it’s like, [00:11:00] well the only people who this actually serves are like people who need a place to deal drugs.

And it’s like, it’s not like the community didn’t need a park, it’s just it got put in the wrong place and built the wrong way. Or, I mean, they’re probably a million other examples, but that kind of field of dreams idea. It’s like, well, maybe we should have asked like the ghosts of baseball players past, like, do you need a baseball field?

I don’t know that we need to run with that metaphor much further, but the, you had this great definition in your paper, where you say conservation professionals. Need to relinquish their role as leaders of environmental work and instead strengthen their capacity to act as facilitators of participatory processes that support the co-design of conservation with, not for, the communities who are most impacted by it.

So I was curious, could you talk more about this concept of letting go of being a leader instead being a facilitator

Kayla Cranston: Yeah, absolutely. Well, it is a good quote. It’s a very Antiochian quote, if I, if [00:12:00] I don’t say so myself, and more importantly, I did create that when I was a hardcore Antiochian did not have much real world experience. And so for years I was on the boat of we need to get people to relinquish control.

Jasper Nighthawk: Mm-hmm.

Kayla Cranston: And then I did some, some real hard research in the real world, and I don’t know about you, Jasper, but anytime I’ve ever asked anybody, any human person to relinquish control over anything, doesn’t go so hot. Um, especially if those individuals are used to having control over what the situation is, right?

And so, I still enjoy that quote. It’s still a very real quote where we need to build our capacity to, become facilitators of this type of approach. And I would say that if I were to rewrite it today, it would say something along the lines of, “not relinquishing control, but really switching the skillset with [00:13:00] which we

have control” instead of going to the CEOs of the world and the conservation leaders of the world and saying, “fantastic, you need to take the control you’ve had for the last God millennia, like many, many years and you need to just let it go.”

I think that is a recipe for a lot reactance, which is just, “oh hell no,” and a failure, because humans don’t like giving up control. And so if we can instead build their capacity to have control over another skillset that is better in line with effective conservation long term,

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah.

Kayla Cranston: that’s what I’d like to head towards. that’s what

Jasper Nighthawk: It is in line with their goals

Yeah. It’s interesting cuz I, I wanted to talk with you about asset framing a little bit later, but it seems to me that as you’re asking conservation leaders to take a different approach, you’re, what you’re describing now is more of framing it as a different set of leadership principles and more of empowering other people [00:14:00] rather than giving up your power. And like naturally when you share power that’s different than being a dictator, but it’s, it’s not the same as you will have no influence or your power is lessened.

Kayla Cranston: That’s right. That’s absolutely right and it’s deeply important. And one of the biggest things that differentiates co-design from other community engagement models is that we, ourselves, we consider ourselves to be collaborators as opposed to people who are standing up and pushing themselves back from the table to allow somebody else to come in and sit at the table, we are extending the table, but we’re still at the table. and, and that’s the thing. Switching the definition of what it means to be a leader, as you say, is really what it’s all about.

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah, I, I throwing your hands up and walking away and saying, well, you do it it’s not the best advice, but, but do kind of draw a contrast. Bill Gates has, you know, $150 billion the stereotype of what the Gates Foundation does is it’ll sort of [00:15:00] parachute into often very poor countries, and they’ll we’ve got this money and we’re gonna run your vaccination program, so get in line, and malaria eradication, or whatever it is. And like, there are, there are worse ways to spend your money if you’ve got that much money, like you could be buying mega yachts, but it also seems like having the richest person on earth decide public health spending, whether or not they’re smart about how they do it, it disempowers the people who they’re intervening on rather than empowering them.

So could you like contrast the co-design approach?

Kayla Cranston: Sure! Well, firstly, this whole idea of empowerment is, can be deeply problematic in and of itself, because I’ve seen it go in a couple of different ways. It is what I wrote my dissertation on, psychological empowerment, and how it can be fostered or not, and there are two different kinds of empowerment, in the research that I’ve done.

One is the kind where “I have power and I give it to [00:16:00] you,” which can be deeply problematic as you’re pointing out,

right? Because first of all, They’re not asking for that, are they? Stop it. Like what? Nobody asks for And if they did, that’s a different story, right?

Because. The other type of empowerment is instead of giving someone else the power that you have, remaining strong in the power that you have, and making room for the fact that the people that have been historically unheard through processes like this, and excluded intentionally, they already have power and that is not the problem. The problem is people that have historically had power and been invited to the table are really, really bad at seeing it. And the structures that we’ve created are intentionally aimed at suppressing that power. And so empowering [00:17:00] something someone is really about unearthing the structures that will help us better see the power that they already have can, help ourselves get out of our own way when it comes to what it looks like to ask other folks to come to the table.

Jasper Nighthawk: So if I’m hearing you right, you’re, sort of saying if you go into a community and you well, I understand that you’ve been disempowered for so long, we’re gonna give you and share power with you,” the people who, like, have been oppressed by the systems in place, but they might say, “Hey, we already have a lot of power. We’ve been running community gardens. We’ve been making all sorts of decisions.” I don’t know why that’s the example that comes to mind, we don’t need you to give us power. We have power. We need you to stop oppressing us.” or to in dismantling oppressive structures.

Kayla Cranston: that’s right. And, it’s in contrast to what many people the power positions, in those examples you’re giving think is happening. Right? It’s “why, why are [00:18:00] you here? Like who, Like who, is asking you to be here?” so you’re absolutely right. It’s very different.

Jasper Nighthawk: Okay. So I want to, I want to get into like the specifics of how this works in conservation work and specifically in your work with zoos. So, this project you’re leading at Antioch, you partner with zoos and aquariums across the country to help them promote communication and develop programming and close consultation specifically with local, historically marginalized communities.

I think we could probably spend a whole episode talking about each of these zoos and your work there, but I wonder if pick out one zoo, and talk about what kind of problems you and the zoo sought to, explore through your work, and then how that work played out in this specific case.

Kayla Cranston: before we start, I just wanna say most of the projects that I’ve worked on that have been successful have been through institutions that do not need me to tell them that they need to change. That they themselves recognizing that, and they are coming to [00:19:00] me for help.

One of the things that they’re specifically seeing is that they, like many other conservation organizations have this traditional approach to creating programing that will impact their community, their, their human community. And it usually goes a little something like this. “We’re gonna create a program, whether it be an educational program, or a conservation program, or job training opportunities for the community, and it’s gonna be great. we’ll use the latest cutting edge research on what works,” And then after we’re done implementing it, we’ll go to the community and we will say, “what did you think about that?” And, you know, jazz hands That’s, that’s it. That’s community yeah, that’s the classic approach to, to what we’re doing as conservationists, right.

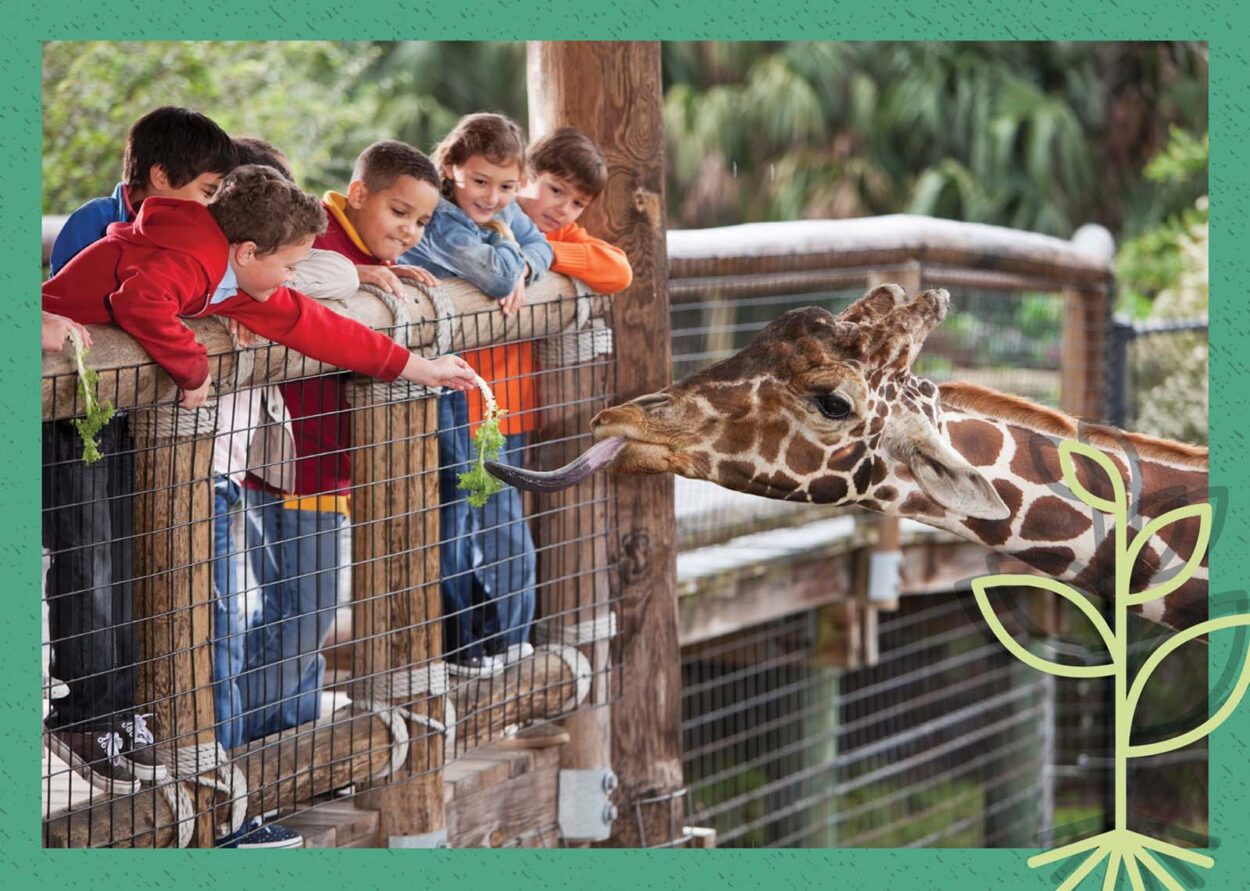

With our human communities. And so the zoo that I work with and other conservation organizations I work with as well, we’re very keen to point that out, [00:20:00] that that is not working long term. And one of the reasons they know that, and this is specific to the Zeus I work with, most of them are in urban areas, right? Within 20 minutes of their main site, they have population that is disproportionately, know, living in poverty, has racial diversity, things like this, that is not reflected in the socioeconomic. demographics, if you will, of the folks who already take advantage of the zoos programming, So we might be having people from around the zoo site coming through the doors, looking at giraffes and stuff, but you look at the roster for the environmental education programming that is being offered at that same zoo, and it is all white, upper class people. Very, very much does not match the demographics of the people who live within twenty minutes of the zoo who could potentially benefit the most from these types of programs. And so the question is why, right? And that was the reason for to [00:21:00] ask the question. And so, why is that the case? bringing this model has really helped with identifying who those individuals are and how can we create programming that is deeply relevant and meaningful to them, so that they will want to put their names on that roster and be a part of this programming that they have now helped to create.

Jasper Nighthawk: And so it sounds to me like, part of the approach there is to expand who “we” is so that the “we” creating that programming can include the people who the programming is serving as well, rather than it being kind of a paternalistic, like, we came up with this idea for you, for you people now sign up.

Kayla Cranston: Right. You’re not, you’re not collecting information about how people feel about your programs afterwards. That might help you, speak to your donors about your impact. However, it doesn’t work with, in fostering a stronger relationship with your community. Instead more, check, early [00:22:00] and often you’re gonna check in way before you even start thinking about doing a program, right? About what is going on. Yeah?

Jasper Nighthawk: Could you a specific example where you found that the people working at the zoo thought that, like, what would a best use of their resources to create one thing and then through working with the community and bringing them into that process, like what, what was the disconnect?

Kayla Cranston: Yeah. That’s a great, great question. So I can give an example um, from an organization that I worked for full-time before I came back to Antioch and started this project, which is where I a lot of my firsthand experience. This place was in an area in the middle of the United States that had like, you could cut the racial tension with a knife and, really bad relationship between the folks in power working at places like the zoos, and aquariums, and conservation organizations there, and those who just lived in the community and didn’t work there. And so I was a part of their team and [00:23:00] one of our jobs as we were creating a new space for our campus to be, that was deeper inside the community that we were finding our programming was not relevant for. And so we had a lot of higher ups in our organization saying things like, “oh my gosh, we have this brand new campus. This is gonna be amazing. Here are all the things that we think might work there.” And I am not kidding, things like balloon rides were brought up, and know, this is the part of the country where black Lives Matter came to fruition, right? Like this where that international movement came out of. And ain’t nobody got time for your balloon, Gonna, that’s not helpful. And so, instead, right, of saying, “what do you need? What do you lack? What, what can we offer? Is it a balloon?” Like the, the, the questions that I was suggesting that they use instead, [00:24:00] really were aimed at, “what’s already working here? Where do you wanna be in five to ten years, and how can we work together to get there? And when you ask those kinds of questions to a community that has been historically disenfranchised, the you know, majority of the time. it flips the script. It really does.

And what we ended up hearing, the very, very smart people that lived in this community wanted was they knew that we had almost like a small city in our organization and an amazing facility staff that was really well skilled at a lot of green job skills. Right? And one of the green job skills was was designing and installing solar panels, right? Compost heaps, permaculture beds, green infrastructure, essentially. And in this community, or largely urban community, that type of skillset just had not made it yet as mainstream type of thing that you got trained in. So they saw that as an opportunity and they said, I’ll tell you. We’re good on [00:25:00] the balloon.

However, what we would like is for our young people have job shadowing, job training in this very unique green job skill set. And so we were excited cuz we knew we had the people that could do that. And so I, you know, marched pretty happily over to the head of the department that could help me with that. And while he was, was deeply flattered that his team skillset was, you know, so honored by, by being asked for. He also got really big eyes on me, Jasper, because there’s just no way in heck right that he or his team were gonna be able to take on this large thing. And this happens at a lot of conservation organizations.

They’re afraid to ask the community what the community wants from them because they don’t think they’ll have the infrastructure to set it up. And so long term, what ended up happening was we had to partner with a workforce development organization that was already in the community doing great work, and together we were able to offer a green jobs training shadowing program that separately, you know, the organization that I was working at [00:26:00] and the workforce development organization in the community would not have been able to offer .

Jasper Nighthawk: That’s a great example. Yeah. Thank you so much for sharing, for sharing that story, and I think it really captures something it, I’m curious also how you go about finding the people to work with, because I know that in many processes, like I live in California and there are these environmental review processes like require there to be, an open space for public comment.

And yet we find that it is routinely the richest people, the landowners, and people with like commercial interests who actually have time and knowledge to participate in those processes. it’s often, know, communities that have been historically disenfranchised that receive the brunt of environmental problems.

And it seems those are specifically the people you’re seeking to engage in these processes. I’m curious what the challenges are and you go about that.

Kayla Cranston: Well, you’ve, you’ve hit it right on the head there, Jasper. The, the challenge is that it’s not [00:27:00] business as usual. We are not saying, “we are an organization for all. If they wanted to be here, they would be.” That’s not what we’re saying. We’re not holding a town hall with one microphone saying, “show up on this one date or a couple of dates, and if you don’t, best of luck with the impact that we’re gonna have on your life,” we’re not doing that. Instead, what we’re saying is, okay, let’s work it as if it were a cocktail party. If you

Jasper Nighthawk: Hmm.

Kayla Cranston: you see somebody across the room that you don’t know that you want to develop a relationship with, in this case, historically disenfranchised community in your neighborhood, right? You don’t know them, y’all in an America cocktail party.

You don’t go straight to them and introduce yourself, most of the time. Instead, you find somebody that you know, that knows somebody, that they know. You get introduced to them in that way. That begins the relationship and you do begin the relationship before you ask them [00:28:00] for anything. You show interest in what they are up to. And so we really do start within, we take about three months to do internal interviews with the staff of the organization we’re working with, asking them questions like, “who should be at the table for these first initial phone calls? Who would be super duper upset if they found out three months from now we started this project without talking with them in the community.” those two questions right off the bat, get you a list to start with.

And then you do this thing that social scientists calls, snowball sampling where you connect with those people and you ask those people the same two questions, who should we be talking That isn’t you who you know, da, da, da. And at some point you will get to somebody who knows the population that you’re attempting to develop a relationship with. And those people we call influencer. And those influencers introduce you to, or tell you a lot more about, what is most relevant to these folks? in most cases, the best cases, what ends up [00:29:00] happening is they say, “you should already know, and if you don’t, here’s some, here’s some ideas for, something to look up about the historical, background of these folks that you say you want to engage.” It’s a lot of work, Jasper, and it is not business as usual because I can tell you right now the things on the job description of many of the people that I work with are not develop relationships with people you don’t know at all and go look up the history of their communities so that you do not offend the heck out of them when you attempt to begin a relationship with them. and idea of beginning relationships is not a thing, right? For many of these organization, it’s like, “we’ll just open our doors and they’ll come,” and, no, no, no, no, no, no. That does not work most of the time if who you’re trying to talk with are folks who have been historically excluded.

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah. Yeah. I love that as a metaphor, of the cocktail party where there’s somebody who you wanna meet. I think it, it emphasizes the fact that [00:30:00] relationships are relationships and. Maybe in the world of business, you can assume that if someone is going to be impacted by you, they will seek you out or they will see your event listing and they will be sure to get in touch with you.

But that, that isn’t something that we can, we can assume, certainly for people who’ve been historically excluded from places.

Kayla Cranston: Yeah, no, you go to them first. Absolutely. through people who know them best and have their best interests at heart that are already in the community, first. so a lot of the first of six months of what I do with organizations is helping them get funding really, for the staff that they can hire that will help them put boots on the ground, go to community meetings in the neighborhoods that they say they wanna engage.

Start showing up to those neighborhood association meetings, those block club meetings. Sit in the darn audience and shut up. Don’t say a word. Just be there. Listen. Figure out what’s relevant, what’s important to the community before you raise your hand at all. Introduce [00:31:00] yourselves if you get, you know, asked, but you’re there to listen. You’re there to build relationships with, with folks that are also going those communities before you ever ask them for their input or for them to come to you to join in any kind of program development.

Jasper Nighthawk: that also seems so respectful, rather than just like, trying to be efficient, like there’s a

Kayla Cranston: Oh yeah, sometimes I can, I can see that that is absolutely the case. Like, “God, Kayla, our donors are just not gonna put up with that.” Like, there’s there’s too time between starting a project and, and getting results. And so that’s when I asked folks to, uh, talking with their donors about what results. And to start looking at indicators that are not butts in seats. So that’s what the psychology helps with.

Jasper Nighthawk: Well, I wanna ask the three questions that you, lead with in these conversations. So you ask, “what is already working in your community? What are the community goals that you have for your community for the next five to ten years? And what [00:32:00] can we design together to reach those goals?”

Kayla Cranston: right.

Jasper Nighthawk: Why are these, the questions that you ask?

Kayla Cranston: Yeah. Well that is an important question. Why? before I answer that, let me just be clear, and it’s very important here. What I don’t wanna see is people taking those questions, just running with them and saying, this is co-design. Because what’s happens before you ask those questions are the six months of going to community meetings and listening

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah.

Kayla Cranston: yeah.

Jasper Nighthawk: After built those

Kayla Cranston: Right after the six months, Right after you, you’ve designed yourself to be more of a part of the community already, then you can start asking people to help you, you. know, recruit for folks who might wanna come to a focus group or do an or a survey, or a listening session. Now, once you’ve got folks after six months, eight months of doing the listening piece, you know, have them come to you and you ask these three questions.

The reason that they’re important is, primarily the communities that I [00:33:00] work with have been historically disenfranchised, and what that means, Literally is that they have been told time, and time, and time again, that they are the communities that lack something. “They have a deficit. They need to be saved. They need to be da, da, da, da.” That is the quickest way to shut down a conversation, let alone a, a relationship with somebody from a community that has been historically told that they are lesser than. So you do not ask things that you would see normally on what in my field they call a needs assessment, which is, “what is missing? What barriers are you coming up against? How can we help? How can we save you? How can we, you don’t say save, but how can we, know, how can we be the knight and shining armor?”

We’re not gonna ask those questions, and primarily because it doesn’t work. It shuts down conversations with historically disenfranchised communities. You and me, Jasper, we’d love to be asked what our barriers are. right? Like we’ve had a certain of privilege where we’re like, [00:34:00] shit, please let ask me, you know, , so that I can get through this. But that’s because You and I

Jasper Nighthawk: say say that, the, at the beginning when we were talking about, know, struggles with, I, I was talking about my anxiety and depression. Like I think if you’d asked me when I was most struggling with anxiety, what are your barriers?” I would, I had no language that

Kayla Cranston: Just shut up. Yeah. Like, “stop asking me that.”

Jasper Nighthawk: Maybe you would’ve arrived if we’d had a deep conversation “oh, I think you may be struggling with this thing. Or like, I, you may want some help, but to start with when you’re, when you’re already facing a lot struggles, like having somebody come in and be like, “all right, give us your problems. We’re gonna solve ’em.” That’s a very aggressive approach.

Kayla Cranston: Yeah. It’s aggressive and it doesn’t work. And one of the reasons it might not work is because the answer usually is, “it’s, you”, my problem is the institutions that you stand for. That’s my Right? So that’s why you don’t wanna, you don’t wanna answer that question. Not really. And so instead you start with what we call an asset-based approach, which is asking, “what [00:35:00] are the, what’s already working in this community.”

Now working in the middle of, you know, Ferguson, Missouri, you look around and you see things that are going so right, and so, well the strongest communities I’ve ever worked in, just so adamant about making sure that their community remains strong over And that means there’s a lot of folks there that are getting a lot right, and you wanna start with that and you wanna build upon that and you sure the heck do not wanna duplicate effort. So if somebody’s already got a Green Jobs training program, stop it. Like, don’t do that. Don’t be in competition with something that’s already going well in that community.

“How do you know?” You ask! What is already going well in this community, right? That’s where you start. And then the idea of, of asking, you know,

next five to ten years, “what are your goals for your community? What would you like to see be happening here?” And then of course, once you’ve gotten an idea of where they’re at now, right point A. Where they’re at now, where what’s really working really well. Where they wanna be point B, in five to ten years, [00:36:00] then you can ask the question, and this is where people get it wrong all the time. They, they ask the, the third question first, not good, but once you get from point to a point A, you get a point B, then you can ask the question, B, how can we work with you so that we as a community, I can be a better neighbor to you, and we as a community can get from point A to point B more efficiently, more effectively,”

Jasper Nighthawk: I could ask like ten different follow ups, but I’m, recognizing that we’re, running towards the end of our time for this interview. And I just wanna kind of end by going a little bit deeper into this concept of figuring out what people need by creating enough space for people to explore and imagine that question with you, and you’re doing it with them. And, in your framework, I really encourage people to go look at this paper if you’re interested in this, one of your five concepts is community demand, where you check to make sure that members of the community you’re working in are [00:37:00] saying that this process is good for their neighborhood.

And to me, connecting it to larger ideas, this sounds, a lot like consent. Like before you do something that affects people, you should make sure that it’s something that people actively want.

Kayla Cranston: And like with consent, Jasper, it’s very important that you’re not asking them directly, “is this what you want?” In a situation where power dynamics require them to say yes, regardless of whether or not they want. Right. heard of this concept of consent, this enthusiastic, “Yes.” is the only yes. That you’re, that you’re looking for. And in our case, in co-design, it is the difference between trying to do good and gotta not produce harm first, before you can go and do good.

So really the idea being asking what are your aspirations, what are your goals, what are your hopes for the future? And then it’s our job to connect what those are to the conservation mission if we ourselves or conservation [00:38:00] organization, right? Don’t ask them what conservation programs they need; that’s a bad idea.

Don’t do that. But this of community demand, the answer, the question that, that they need to be able to say absolutely agree a hundred percent is, my neighbors have told me that this is good for our community. And they have evidence, Jasper, they’ve been told by others in their community that what’s going on is good for their community. That’s why it’s community demanded instead of like residential demand or resident demand. Cuz it has to be the community that’s in on it and they want it.

And they’ve, they’ve, they see how good it is for their community, that’s community demands a huge bar, high bar, really high bar, really one people get wrong,

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah, I, I think we’re kind of alluding to the way that we talk like affirmative and enthusiastic consent in like a sexual context, which we’ve talked a actually about sex on this podcast, so it’s, I, I don’t think it’s an unrealistic [00:39:00] metaphor, but you don’t have that kind of enthusiastic consent, then I think you’re actually protected by not going forward and just saying, “maybe let’s keep talking or maybe there’s a next time.” I love the way that your concept of community demand and actually waiting till the community’s demanding something rather than, know, “oh, the community says that’s okay if you wanna do that

Kayla Cranston: Yep.

Jasper Nighthawk: Um, that just seems, it seems transformative and, and like it adds potential beyond just conservation

Kayla Cranston: Right, Right, right, And I think you’re right. Stopping. immediately. If, if there’s not an enthusiastic yes and it goes the question being, you know, right. We can sit here and talk about this all, theoretically and conceptually, and that’s all well and good. However, the question that always comes once the rubber hits the road is, “how the heck do you do that? What are you doing that people are coming to your back door going, I really want you to do this conservation project. It’s really important for me.” And the and the answer is, they won’t [00:40:00] be they won’t be, they won’t call it conservation. They won’t, they’ll call it what they need in their daily lives. What they want for their futures of their communities. They want jobs, they want, you safety, they want, financial stability. They want all of the things that you and me as humans can understand, as aspirations, and it is our job to connect that to our conservation mission and create a program that really does aim to hit both goals.

Jasper Nighthawk: Yeah. Well that is a beautiful place to end this. thank you so much for coming on, on the podcast. Kayla, it’s been a pleasure hearing just a little bit about this. Um, I hope we have a chance to talk again.

Kayla Cranston: Thank you, Jasper.

Jasper Nighthawk: Antioch University School of Environmental Studies and Sustainability, which Kayla is faculty in offers study of conservation psychology at the certificate, bachelor’s, master of science, and PhD levels. We have links to those programs. In our show notes, we’ll also [00:41:00] include a link there to Kayla’s zoo biology paper, which we’ve been discussing and to our common thread article, looking back at the co-design project after its first year.

We’ll also link to a course specifically on co-designing conservation that Kayla teaches at UC San Diego extension. We post these show notes on our website, theseedfield.org, where you’ll also find full episode transcripts prior episodes and more. The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch University. Our editor is Johannah Case. I’m your host Jasper Nighthawk. Our digital designer is Mira Mead. Jen Mont is our web content coordinator, Sierra-Nicole E. DeBinion is our work-study intern. A special thanks to Karen Hamilton, Emilia Brian, and Melinda Garland. Thank you for spending your time with us today. That’s it for this episode; we hope to see you next time, and don’t forget to plant a seed. So a cause and win a victory for humanity.

From Antioch university. This has been The Seed Field Podcast.[00:42:00]