Activist and educator Jane Paul thinks an economy that works for everyone is not only possible but achievable, through creative solutions that we can implement starting today.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google | Simplecast

Episode Notes

How do we build sustainable, just economies? This is a question that seems to call for big, systemic solutions. But those can feel out of reach and beyond our scale to affect. The activist and educator Jane Paul says that there is another option: while fighting for larger change, we can build small-scale solutions in our communities. From worker-owned cooperatives to land trusts and mutual aid societies, we can start building a more equitable economy right where we are, and right now.

_____________

Visit Antioch’s website to learn more about the Undergraduate Studies program at our Los Angeles campus where Jane teaches. Learn more about Jane’s work here.

Links mentioned in the interview: LA Co-op Lab, Los Angeles Eco-Village, Cooperation Jackson, Hope in the Dark, and Beautiful Solutions.

This episode was recorded on October 27, 2022, via Riverside.FM and released on December 1, 2022.

The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch University.

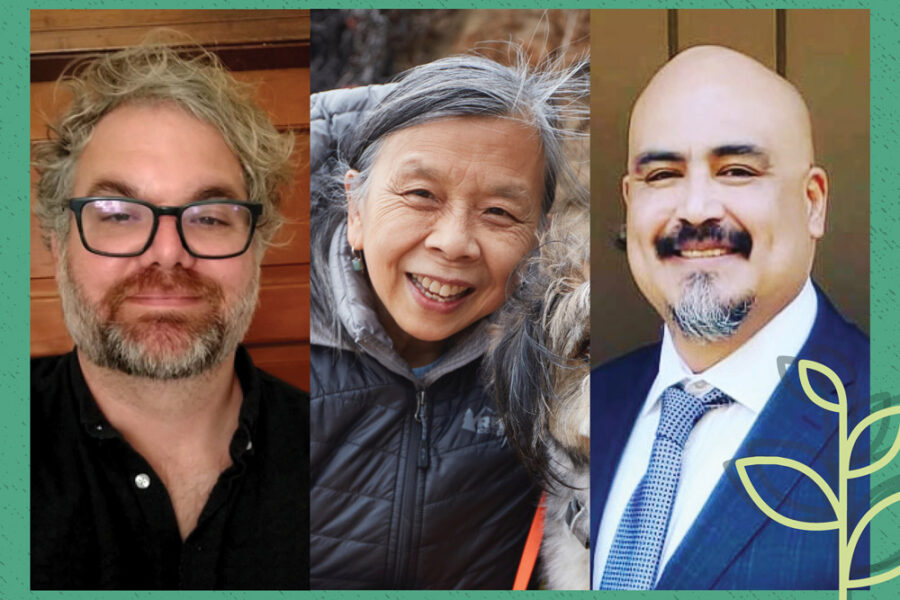

Host: Jasper Nighthawk

Editor: Johanna Case

Digital Design: Mira Mead

Web Content Coordination: Jen Mont

Work-Study Intern: Sierra-Nicole E. DeBinion

A special thanks to Karen Hamilton, Amelia Bryan, and Melinda Garland

To access a full transcript and find more information about this and other episodes, visit theseedfield.org. To get updates and be notified about future episodes, follow Antioch University on Facebook.

Guest

Jane Paul is a college instructor, an activist, and an advocate for economic, environmental, and climate justice, housing rights, and for incarceral system reform. She teaches at Antioch University Los Angeles (AULA), in the undergraduate Urban Studies concentration, as well as in the Master of Arts in Urban Sustainability program. She is teaching, researching, writing, and developing curriculum on the solidarity economy, climate, and human rights.

S4 Episode 7 Transcript

Jasper: This is the Seed Field Podcast, the show where Antiochians share their knowledge, tell their stories, and come together to win victories for humanity.

[ music]

I’m your host, Jasper Nighthawk, and today we’re joined by the teacher, writer, and community activist Jane Paul, for a conversation about the concept of an equitable economy, and the steps that we can take to build one.

This is a topic that has been on my own mind a lot lately. I mean, obviously I’m a human alive in the year 2022. These days, seemingly everywhere you look, you can see how unequal and unjust our society has become. You can see it in our medical system, where people are routinely denied life saving medications and treatment because of their financial status. You can see these inequalities in our education systems, where rich people congregate in expensive areas and use their property tax money to fund lavish schools, while those in poorer areas are forced to send their children to schools with radically fewer resource. I could keep going through almost every aspect of our society, from the environment, to our system of elections itself. But there’s one more thing that I think is especially pertinent to this conversation with Jane, who has worked on this. We both live in Los Angeles and for myself, I’m lucky to have a rent controlled apartment, but I don’t see a realistic path to owning a home anywhere within this entire city. And I have advanced degrees, a steady job, and a spouse who works full-time. At the same time, it feels insane to complain about my own situation when almost seventy thousand of my neighbors are currently, tonight, living without shelter, or un unhoused at any rate. And often these conditions are squalled and really dangerous to their own health. Being homeless is a giant health risk. And at the same time we can, get in a car, take a bus over to Beverly Hills or Malibu and see some of the most opulent estates imaginable. So all of this to me leads to this question that our guest has been working on for many years and asking through her activism, her writing, and in classes that she teaches here at Antioch. How do we build sustainable and just economies?

So, let me introduce Jane. Jane Paul is an activist advocate for economic, environmental, and climate justice, for housing rights, and for incarceral system reform. She’s also a longtime teacher at Antioch University’s Los Angeles campus at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Prior to teaching, Jane was an environmental policy consultant, and among other roles, she led the green economy initiatives at the Green LA Coalition. She’s been appointed by multiple LA mayors to serve in one role as commissioner and vice chairperson of the City of Los Angeles Rent Adjustment Commission, also as chairperson of the City of Los Angeles Green Retrofit and Workforce Development Advisory Council.

Jane is herself an Antioch grad. She graduated from the BA in Liberal Studies Program here at Antioch Los Angeles, and she holds an MA in Urban Planning from UCLA. Beyond her teaching, Jane has chaired our sustainability committee, co-authored the LA Campuses’ Climate Action Plan, and served as chairperson of the Bridge Programs Council. Okay, so that was a lot, but welcome to the Seed Field Podcast, Jane. We’re so delighted to have you here.

Jane: Thank you so much. I am absolutely honored to be part of this lovely thing.

Jasper: So as we jump into this, we really like to start by disclosing our positionality and we’re gonna be talking about the ways that our society is structured. I think it’s important to say the roles that, or the kind of places that we fit into that. I will start. People listening who can’t see me should know I’m a white, cisgendered man. I’m not straight, but I am married to a woman, and I move through the world with a lot of straight privilege. I’m not living with a disability right now. I do struggle with anxiety and depression, and I also should mention that I have steady income and steady housing. Jane, as much as you’re comfortable, could you disclose the position you’re coming from?

Sure. It’s a little complicated, isn’t it? This thing about our identity. Starting out, my pronouns are she and her. I live in Los Angeles, which is the traditional and unseated territory of the Tongva people. We honor their stewardship and their history every day, I hope. And identity, it’s tricky. So, I’d love to say I’m from New York , and that’s my identity.

Jasper: That’s part of identity.

Jane: Yeah. And my recent ancestors are from Eastern Europe, but my indigeneity, I believe is Middle Eastern because I’m Jewish. So there’s that, but I look white and so, I definitely appreciate that you talk about going through the world with a level of privilege. I totally do. And I really try to be humbled by that. So thank you for raising that. For all of us. For us here, and the listeners.

Jasper: . Well, thank you for disclosing what you did, and I appreciate also, I think that identity is a lot more complex than a bunch of kind of check boxes. So, your New Yorkness, your Eastern- European- Jewishness are totally vibrant and I think, more beautiful necessarily than saying I’m white.

So, I wanna ask you, I gave this kind of introduction setting up some of the problems of our world and I wanted to ask you, how would you frame the biggest problems that we face and that I know we’re gonna be talking about in this interview today?

Jane: The biggest problems we face are humanitarian problems. I like to look at those through an lens of the economy, because I find that sheds light on why we’re in this pickle that we’re in, where so many people are suffering, and there’s so much inequity. And also the economy is a place that we can make change. That we can fix. So right now I would say we need a new economy because the one we have is not working for most folks. And that’s sort of my big, platform. Sadly, I don’t have a bumper sticker answer.

I feel like that a neat way of condensing it down to say, “the biggest problems we face are humanitarian”. Things that get in the way of humans thriving, people lacking access to the materials of survival, and being able to thrive. And the way that I find most productive to think about it is addressing it through an economic lens. Do I have that right?

Jane: Yes. Yes. Thank you.

Why the economic lens?

Jane: It’s interesting, Jasper, I’m gonna go to my history for one second, back in the early eighties. I actually worked in the motion picture industry in New York. And before that I had been a salesperson selling shoes in the mall, I was a waitress and a bartender for years.

So after, getting going in the motion picture industry for a few years, I actually was making a little bit of money, and I was really raised, thankfully, with a sense of responsibility, social conscience. And so I went to a seminar, about socially responsible investing, and what I learned there was that there was this amazing thing called “community banking”, and it just set off all sorts of fireworks for me, and I became a student of this idea of community economic development and I thought, and still do, that that was a way to solve poverty.

That’s what brought you to get this, to pursue this planning degree?

Jane: Yes, absolutely. So community economic development lives within urban planning.

Jasper: Yeah, so you came to this realization that community economic development was the way to address poverty and that it was a bigger mission on Earth for you to work towards addressing poverty, than to necessarily be in the motion picture industry. So, can you explain a little bit more what community economic development means to you? And like the mechanism which that actually does poverty?

Jane: What I believe is that community economic development is what we see around us, and this comes to an important thing. I like to always say when we’re talking in classes, or even amongst friends about the economy, and that is seeing our place in it. So, everything that happens around us has an economic aspect to it. Is there a store nearby where we can buy the things we need?

Who owns the store? Where do the profits of that enterprise go? As the person who shops at the store, do you have enough money to get what you need there? That has to do with your job. Your job is a definitely, a local community thing. For you, even if you’re working for a giant company that’s based in Arkansas. So community economic development happens all the time. It happens whether we have a bus line near our house or not. What time does the bus come?

Housing, which you mentioned earlier, is such an enormous issue for everyone, globally, right? There are housing shortages globally. That’s definitely a very much of a community economic development thing. But all of these aspects, the workplace, commerce, the marketplace, housing, infrastructure, they all have local, regional, and larger power structures that influence those.

Jane: The mechanisms of community economic development have to do with us as individuals, and as community members taking charge, and or feeling disempowered. And so that really is a segue to this idea about a solidarity economy. A new economy where we are working together to solve the problems of equity and access to food, to jobs, to capital, to safe housing, et cetera.

I want to go more into the solidarity economy, but I also wanted just hearing you talk about it, I thought, well, there is something that’s not really community. It is economic development, but it’s not, it doesn’t, it’s not framed around community. And we might call it like corporate economic development, or robber baron economic development, where it’s not actually meant to serve the people in a community, but is more likely to be patting the pocketbooks of somebody who’s already very wealthy.

Jane: Absolutely great to raise that. It might be considered the opposite of community economic development. When we follow the money, right? So where’s the money going that we spend in our communities? Is it going to our neighbors, or is it going to somebody whose bank account is in Switzerland or the Cayman Islands, or even just in, Baltimore, right?

So what we wanna do, what we hope to do, is to change that power structure. What you’re describing, the corporatocracy , is really neoliberalism. So the capitalist economy that we’re in is a tool for a political power project, often known as “neoliberalism”. And so we can think about it just in terms of

Jane: money and where the money goes. But what happens is that money or lack thereof, either builds power or disempowers.

Jasper: Okay. And I think that brings us to the solidarity economy. I think it’s maybe beyond the scope of our conversation here today to really deeply understand, how capitalism functions, and, to go into those power dynamics and kind of self-reinforcing structures.

But maybe we can see it if you sketch for us the alternative, the possibility of a economy. How would that differ from the economy that we have in most of this country today?

First of all, I agree that we can’t talk in a short time about capitalism, neoliberalism, but if you have 15 hours, we could get started. So what’s different and what we talk about in the solidarity economy, as I said, is this idea of working together. Capitalism and current ideas about success are very much focused on individuals, and building wealth.

Jane: And so if you think about the image that we’re often given of getting to the top of the heap being the most successful, the image itself is that of someone climbing on top of someone else, and not learning from them, but stepping on them, right? So we often say, we ride on the shoulders of our ancestors.

That’s really different from stepping on the people below you so that you could get to the top of the heap. So the idea of solidarity is that, folks are working together and what that looks like, in very practical terms, for example is worker ownership. Almost everybody works for somebody else.

Some folks are self-employed and that’s great. And then most people are working for some entity that may or may not be friendly, that may or may not be nearby, that may or not, may not be respectful and so on. So, one way to tackle that struggle is worker ownership. And what that means is you have a worker owned cooperative, you have a business, and all the workers are co-owners, and they all make decisions together and they all equally, more or less, share in the profits. We see a lot of those in, the Bay Area. There’s lots of them. If anyone’s ever been to an Arismendi Bakery, in the Bay Area, those are worker own co-ops. We have a few in Los Angeles, for whatever reasons, it’s, we’re a little slower to get going on this, but like so many other things in the new economy, the recent economic, struggles are actually increasing the opportunities for things like worker ownership.

People are seeing, more and more, the need to have more control over their lives, over their health, over their salaries, over their working conditions. And so although it’s hard to picture a bunch of folks making decisions together. It is possible, it requires training. have to go to school to learn how to live in a democracy, to make decisions by consensus.

And, fortunately that training is available to folks. We have a great, great, amazing, local entity, the LA co-op lab that offers technical assistance, and financial assistance, to worker owned co-ops, in Los Angeles and beyond. There’s amazing examples in Europe, in Spain, they’re quite old.

There’s an entire region that everything is cooperatively owned. Not just the workplace, but the banks, the universities, and so on called Mondragon.

Gone. Yeah, and I maybe we can talk about that a little bit more, but I wanna draw you out draw you on the difference between , the way that, 99% of businesses, in the US today are set up and the model of worker own cooperatives. I think a lot of people are familiar with the idea of unions, and having worker voice and worker power through unionization. How does a worker uncooperative differ from a union?

The union represents the workers and gives them a space for their voice to be heard and their concerns, and a seat at the table. In a worker own cooperative, every seat at the table has a worker in it. And in fact, exact-, they own the table.

Jasper: Okay. Okay. So I mean , that seems like revolutionarily more than what even like the union movement in the US has managed to achieve. It’s the end of, having a separate class of people who are owners.

Jane: Yes, and there is a lot of solidarity between the labor movement, organized labor and unions, and the work owned cooperatives.

Jasper: One of the questions that I have is it’s in many ways a revolutionary idea. If this caught on in a massive way and it suddenly every business was worker owned, it would be a complete revolution in like the way that money is split up in this country. Who has power to dictate working conditions just like the conditions of a lot of our material lives. And so I wonder, when we think of revolution, we often think of, 1917,fighting in the streets and then, the czar’s head being hoisted over the winter palace. I don’t, I think I made up that last detail, but, the complete overthrow of the existing order. But you’re talking about these worker on cooperatives in the Bay Area, some emerging here in Los Angeles, and around the country, and they’re existing within the neoliberal order, even as they offer an alternative to it. Do you think we should be pushing for that kind of big R revolution or, how do we dismantle current systems of oppression, these series of smaller steps?

Jane: Dismantles a great word. Thanks for using that. I wouldn’t in this space advocate for the big R revolution. I think that’s just not our, it’s not our moment to sort that out because that’s so complicated. And also revolutions are often not necessarily led or instigated by the people, but more often by folks who will be less harmed in fact, and have more privilege.

Jasper: And sometimes use the people as a tool. Yeah.

Jane: I do think that dismantling is possible, but it’s, these are tiny, gentle, bits of change, that when combined, have the capacity for larger change. So when we talk about a organization that has eight bakeries, in the Bay Area, does that undo Walmart, or Monsanto?

No. But those eight bakeries have, let’s say a hundred and sixty workers. That’s a hundred and sixty families who are learning how to be different, operate differently in the world, who have a level of autonomy. Imagine what the children in those families learn about how, what’s possible in the world. So we like to talk about the possibility of a better world.

If you have a hundred and twenty families in Los Angeles who are living in a, in cooperative housing, and the land that the housing is on is, managed by a community land trust, again with shared decision making and shared ownership. Again, now you have a hundred and twenty families in that space who are learning to operate differently, and so maybe those adults are taking that thinking to their workplaces.

Maybe those kids are taking that thinking to their schools and to the playground. So, it sounds tiny, but it really isn’t because across the country there are worker owned cooperatives across the country. There are community land trusts, across the country there are different ways that people are learning to be, out of necessity.

If the existing economy worked for us, we wouldn’t necessarily be doing all this, but the current economy’s not working. We have a confluence of crises where the economy is causing, global climate disruption. And so the tentacles of this solidarity movement are actually very powerful. Even if you just take the idea of shared decision making and then you start to talk about what democracy looks like.

So we can talk about the workplace, we can talk about housing. We can hopefully talk about access to capital, because lots of folks will say, “Oh, that all sounds so lovely, but where are you gonna get the money?” That’s what Uncle Joe always says about your highfalutin lefty ideas. And so there’s a lot of steps to this. It’s, it is actually, beautifully complex and meaningful.

Jasper: I think that’s very lovely the way that you’ve put that. And I want to dig into a couple of the things that you brought up there. So one thing that you brought up is, the idea of people living in collectively owned housing, and I think you’re referring to a development you’ve written about here in Los Angeles called the Los Angeles Eco Village. And can you just explain to us a little bit more of what that is, where it is, and how the ownership is structured.

Jane: I’ll tell you what I know, and of course I don’t know the minutiae of it, but, I wanna say it’s about sixty units in two or three buildings that are connected in Koreatown. So Vermont, and between first and second, which is a very dense neighborhood, very diverse, lots and lots of different, people from different ancestries and also, a place that has a lot of housing instability, and like almost all of LA a lot of gentrification and displacement happening. So the Eco Village actually has been there for many years, and, the apartments, which are all sizes, so there’s singles and there’s families and there’s couples, they are part of a cooperative, meaning that their shared ownership and shared decision making. The land itself is managed by the Beverly Vermont Community Land Trust, and there are lots of examples around Los Angeles of land trust and land trusts are, as they sound managed by people from the community, some residents and, but not necessarily again, with shared decision making. And what’s important, both the cooperative model and the community land trust model, is the intention is to preserve the land for affordability and perpetuity.

Jasper: So it seems like that model kind of flies in the idea that land is a resource that is meant to be exploited and whoever can ring the most money out of the land, like this the idea of like an auction for federal land, whoever can bring the most money out of it, or things they can, should have the right to extract as much value as they can from it.

Jane: Yes, yes.

Jasper: Okay. When we were talking earlier, you said something very beautiful about land as being something sacred, and nourishing, rather than as something to be exploited to the maximum it can be.

It’s a quote from Winona LaDuke who’s a Native American leader, author,

Jasper: And Antioch alum.

Jane: Winona LaDuke?

That is my understanding. we’ve

Jane: Okay.

tried to get her for the Antioch Alumni Magazine on multiple occasions.

Jane: Oh, that’s fantastic news. I didn’t know that. She talks about commodifying the sacred. And so land can be considered sacred, but many folks consider land to be only an asset, and something that can be traded, and utilized purely to extract, the good word that you used, to extract the greatest amount of currency. And so in that scenario, affordability and that right to housing, and I love that the right to housing is also framed as the right to health these days, that housing is healthcare.

Speculative real estate / land marketplace does not necessarily consider housing to be a human right, and does not necessarily consider land to be owned, in the commons. We’ve had the commons taken away from us. And split up, and divided, and sold, and resold. Each time to the highest bidder. So of course, folks who don’t have a lot, are left out of that scenario.

Jasper: Thank you for expanding on that, and I also wanted to draw out, you brought up our environmental crisis, which is a mega crisis that has been unfolding my entire life and now seems to be just on a terrible role. Obviously with global climate change, massive biodiversity loss, desertification, all sorts of things happening and with the scale of that crisis, I think a lot of people turn to despair because they feel like there’s just no pushing against it. That any one person or even small group of people can do that will make a meaningful difference. Not that I necessarily totally buy into that, but I’m curious how the solidarity economy interacts with the environmental crisis and maybe offers some solutions.

Jane: That’s a great thing to think about and talk about because there is no separation these days from between one crisis and the other. So if you’re talking about social justice, for example, we’re talking about climate justice, we’re talking about economic justice. We’re talking about racial justice. We’re talking about educational justice. All of these things are now deeply embedded with each other in terms of the processes and also in terms of the problem solving. The despair is really real. And I want to just acknowledge that, how true that is. There’s a lot of sadness for everybody.

Joan Baez, another great leader said, “Action is the antidote to despair”. So, with that in mind, just have a big neon sign here that says that, I have found the solidarity economy to be a great place to be activated. And the connections are that when you are looking at the local economies, you’re looking at what their impact is on the community. Not just whether people are earning enough money, or have the things they need for, the goods and services that they need for wellbeing, but also what’s the greater impact.

Jane: So, if you have a worker on cooperative, for example, it’s unlikely that’s a toxic polluting business, because everybody goes out the door and lives down the street, and so is not going to manage a place that is toxic for themselves, or their family, or their neighbors. And on a bigger scale, if we can take some of the economic power away from the large corporate entities that are the polluters, then we can in small ways, big and small ways, start to undo some of the extractive structures causing climate disruption. And climate change impacts people, who most impacts people who have the least amount to do with the climate change happening. So the people who are spending the least amount of money, flying the least on airplanes, not building the most expensive, crazy things where things should not be built. And, even simple, bicycling, walking, right, instead of driving big, spewing cars.

Jasper: So to some degree, if you’re empowering those people who are most likely to be bearing the brunt of these changes to our climate, and least likely to be the ones actually causing it, that also shifts the dynamic of power.

Jane: Absolutely. It changes the narrative. So we wanna reframe the story that’s told about what we talked about earlier about this idea of what success is, right? And having the most money, most biggest house, most number pairs of sneakers, doesn’t buy happiness. It certainly doesn’t create happiness for other folks.

So we are starting to also just change the narrative so that we can see again, as we have for thousands of years, the beauty of taking care of each other and the beauty of working together on something. a lot of what we saw during the early days of the pandemic were that people jumped right in to take care of each other.

And we see this when there’s a natural disaster. We see this in a lot of, crises that people’s first instincts are not necessarily to just protect themselves. But in fact, they think about the older folks down the street. They think about the people who have babies who can’t manage for themselves.

They think about who needs food, who needs healthcare, who needs to be taken somewhere, who needs just to have their handheld. This is something we’ve always done for each. And even in the simple basic ways where a baby is born and everybody goes over there and brings a gift, or an old person is sick or somebody passes away and everybody goes over there and brings some food.

Those are ancient human instincts to take care of each other. And in doing so, we’re caring for ourselves as well, so it doesn’t counter our kind of tribal survivalism because we are gonna rely on those folks to help us one day.

Jasper: We’re social beings. we’re not just like individual atoms trying to accumulate as much stuff. That’s very beautiful the picture you’ve painted there of how we as communities can support each other. And I think of, Rebecca Solnit wrote a book, which I’m forgetting what it’s called. Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the way that there’s a narrative that, as New Orleans, became a place of great human suffering and probation, that there were people at each other’s throats and looting, and rape, and all sorts of horrible things. And it’s not to say necessarily that looting during a natural disaster is the most horrible thing in the first place, but, in fact, there are so many examples of people feeling energized and feeling like they had purpose in helping each other and being un unspeakably generous, just like generous beyond generosity.

I think that kind of leads to a question that I have for you, which is that I think around crises, and I also think of the financial crisis in 2008, or the Covid 19 epidemic, and certainly the early months of it, there often is, we see across our society, this upsurge in interest in changing the economy, protecting people who are most at risk and then I often see that energy dissipate. It’s like once the crisis is passed, people often, “oh, the economy is okay again for me, so I’m not interested in working to change it as much”. And it, it seems to me like this idea of the solidarity economy, and specifically, these immediate projects, being part of a worker on cooperative, being part of a community land trust, or like you working to bring attention and education to people around all of these things offers maybe something more sustainable than crisis moment, because I just think about how the forces that sustain our current system have massive bank accounts behind them and they’re able to hire packs of lawyers who, and lobbyists, and everyone, who doesn’t take a day off, or doesn’t run out of energy and have to turn back to the rest of their life. I guess my question is, does the solidarity economy offer a different way forward for activism?

Jane: Yes, it does. There’s a lot there that you were just unpacking. So I would say that when, crises happen, and I just heard, gentleman who’s works with, folks in Jackson, Mississippi, is from Jackson, Mississippi, where they have recently had a terrible water crisis. But in fact, Jackson, Mississippi and a lot of the American south has been an economic crisis for quite a long time.

So there’s a group called Cooperation Jackson that does really great kick- ass work there. So see, Kale Akuna was being interviewed about this water crisis in Jackson where they, there’s no water. And he said that the media gave them about a week where they were potentially front-page news on a couple of papers around the country.

“How’d it happen?” And that was about it. It was about a week, and then some other crazy thing happened, some other part of the country, he said. But that week in the media is not the most significant thing. What is significant is that the crisis have been building for years, and we will be solving the problems of those crisis for years to come.

So I think being activated. In community with other folks, kindred spirits, like-minded people, is what we need to keep doing, and that the media, for example, sometimes gives us space, and sometimes does not. Sometimes they just have to move on because the information overload. The world is changing so quickly, et cetera, et cetera.

And so because it’s not in the media, doesn’t mean it’s not happening. And I think that’s important for people, in that, and I think the Rebecca Solnit book is something like Hope in the Dark, “Finding Hope in the Dark”, something like that. So we are, purveyors of hope in the solidarity economy.

We are gonna talk about how a better world is possible forever. It’s up hill. And always has been, and always will be. There’ll always be inequity, but we have work to do every single day, and when we are not alone, because it’s a terrible feeling And that’s part of that despair that you referenced earlier.

It’s a terrible feeling to get outta bed in the morning and say, “I am the only person who thinks things are really screwed up, and wants to change them”. That’s not a good feeling. So if you can go to a place, whether it’s a physical place, or an intellectual space, a classroom, a workplace, a community meeting, an online entity.

Find your collaborators. Find your co-conspirators. Find, your compatriots in the struggle. To me is the way to keep going. And in fact, there’s so many beautiful people doing so much amazing work. There’s a website called “Beautiful Solutions”. This changes, everything’s connected to Naomi Klein a little bit, but if you were to just look up “Beautiful Solutions”, it actually shows you stuff that people are doing all over the world all the time.

And, it’s super exciting. And while It’s not possible to not feel, that it is too uphill on many days, the fact that we are in good company, with people who are not only compassionate, but really smart, and really innovative and really creative, and understand that the economy is relational.

The marketplace has to do with a social contract. And so as you said, we are social creatures and we are better off if we’re in agreement that our contract is gonna be fair to each other, to one

Jasper: That’s so beautifully put. And I feel like I could like pick your brain for certainly another fifteen hours about capitalism, but, just hearing this, I do feel hope and feel a renewed excitement about the work that I myself have done, and continue to do, but also a desire to be more involved. I will certainly look up that website. I wanted to ask you about your role, in this work and in, in building towards the solidarity economy and specifically your decision to focus on teaching. I think it might seem more direct to just start a worker own cooperative of your own, or to become a community organizer and spend your days doing that. So what is it about teaching and working with students that has made you feel like this is the way that you want to contribute to bringing this change to our world?

I started out as just a consultant in the Urban Sustainability Master’s program because I’d worked with a lot of different groups and had a lot of experience coming from my economic and environmental justice policy background, and they said, “would you like to teach?” I said, never have, but I’ll give it a shot.

Jane: So I actually had a chance to teach before I knew what was most important to teach. And so I’ve learned that. So it’s a little bit of just a different, trajectory. I feel like teaching is like community organizing. It’s, and it’s a little bit like spreading the gospel. If folks don’t know about something, then they hear about something that touches them in a certain way.

It sparks something. And then people start to nod their heads, and people’s eyes start to light up, and people start to think about what’s possible in the world and what their own potential is. And this idea that yes, I, if I had a great idea for a business, sure I would, it would definitely be a worker own co-op.

But I don’t at the moment. And, and I love this, I and I do some organizing work, community organizing work around housing. it’s similar to teaching. It’s sharing, it’s sharing knowledge, it’s sharing resources. And in that way, we’re always learning together, right? So also being a teacher means that I get to always be learning.

Cause all these topics, I teach about the economy, I teach about social change, I teach about incarceration. All these things are super dynamic, and so I have to always learn. And so I feel very much a part of the learning community, and I see students who get activated from what they learn. My class, other people’s classes all the time.

People are always doing amazing projects based on what they have learned, or that spark, or that inspiration that they got in school. Whether it’s in our bridge program, or an undergraduate or graduate. Across the board, people get excited and I love to be a part of that excitement. It feeds me and my soul too.

Jasper: That’s so beautiful. this, I think this is a great place to leave it. Thank you so much, Jane, for coming on the podcast today.

Jane: Oh my gosh, this was a huge pleasure and if anybody would like to talk to me for fifteen hours, I’m down. I’d be happy to talk to anybody about all of this at great length or maybe see some folks in my classes.

[music]

Jasper: To learn more about the undergraduate studies programs that Jane teaches in, you can visit Antioch’s website, antioch.edu. And we will link to the specific program page in our show notes. We’ll also link there to some of the resources and organizations that Jane mentioned, including the LA co-op lab, the Los Angeles Ecovillage, Cooperation Jackson, the book Hope in the Dark, and the website Beautiful Solutions.

We post these show notes on our website, theseedfield.org, where you’ll also find full episode transcripts prior episodes and more. The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch university. Our editor is Johanna Case. I’m your host Jasper Nighthawk. Our digital designer is Mira Mead. Jen Mont is our web content coordinator. Sierra-Nicole E. DeBinion is our work study intern. A special thanks to Karen Hamilton, Amelia Bryan, and Melinda Garland.

Thank you for spending your time with us today. That’s it for this episode, we hope to see you next time. And don’t forget to plant a seed, sew a cause, and win a victory for humanity. From Antioch University, this has been the Seed Field Podcast.